Social Networks’ influence on Family Planning: Some fascinating findings from Tékponon Jikuagou

Think about all the people you trust for advice, love, and support. Then imagine the people that those people trust, and the people that those people trust, and so forth. You’re probably left imagining a complicated, tangled web of social connections.

In rural sub-Saharan Africa, information about family planning and gender norms often travels through these trusted relationships, by word of mouth. Through the Tékponon Jikuagou Project, the Institute for Reproductive Health (IRH) and partners CARE and Plan International aim to better understand these networks and how they can be leveraged to spread helpful, accurate information.

Understanding social networks

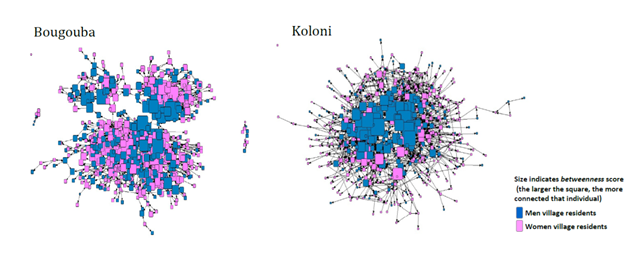

Our research began with a social network census in two villages in Mali, where researchers visited all residential dwellings and interviewed consenting adults about two topics: (1) their family planning behavior and attitudes, and (2) the people who influence their lives. IRH used the computer programs UCINET and NetDraw to analyze and chart maps of these social connections and networks in the villages.

What does a map like this look like?

Each node represents a single person while links between them show relationships between individuals. Blue dots show male village residents; pink dots show women village residents. The larger the dot, the more often the person has been named as a trusted individual. It’s clear that the village of Koloni is one large network, whereas Bougouba is three interwoven networks. Social network maps provide both a visual and a quantitative snapshot of human relationships, as they illustrate how people are connected and share information with each other.

[The names of the villages have been changed to protect confidentiality.]

Want to test your knowledge on social network maps? Take our quiz!

5 Takeaways: Formative Research

You’re invited to take a deep dive into our recently published report on these findings. Using Network Analysis for Social Change: Breaking through Barriers of Unmet Need for Family Planning in Mali analyzes how social networks have impacted gender and family planning use in two rural villages in Mali. (Note there’s a French version of the executive summary, too!)

Here are a few highlights:

- Family/friends = most trusted for family planning information. Research shows that when seeking information about family planning, respondents turn first to family and friends. Although participants did see health workers as trusted sources, they do not necessarily seek them out first when they have questions about family planning methods.

- Fewer connections means greater risk for family planning unmet need. Take a look at the above network maps. See those outlying clusters of people who aren’t linked to the greater social networks? These people are most at risk for unmet need, in part because they are less likely to be exposed to new ideas about fertility and family planning.

- Healthy Timing and Spacing v. Family Planning Methods – language matters. People can be supportive of healthy timing and spacing of pregnancies but not necessarily approve of family planning method use. According to this research, the term family planning is associated with limiting births. Many people see limiting births as a separate concept from spacing births; where the latter is generally socially acceptable, the former is not.

- Gender drives social networks. Gendered power relations kept women from obtaining or using a method, even if they were motivated to do so. A lack of communication often led to incorrect assumptions: women and men believed their partner was opposed family planning or wanted more children than was actually the case.

- Women and men have different social networks. In both villages, men were more connected than women. While men tend to discuss fertility, child spacing and family planning one-on-one with friends of the same generation or in small peer groups, they rarely discuss these topics with their family or in formal group settings. Women, on the other hand, talk frequently with female family members, including mothers, mothers-in-law and sisters-in-law. Women are also more likely to discuss and debate ideas in formal group settings.

4 Takeaways: Baseline Household Survey

In 2012, the Tékponon Jikuagou Project relocated to Benin and began by conducting a baseline household survey. These findings add to the growing body of knowledge around using social networks to increase family planning use.

Here are a few of the top survey findings:

- Unrecognized need for family planning. Many participants perceived that they had met need or no need for family planning for a variety of reasons, but were in fact at risk of becoming pregnant–especially during the postpartum period.

- Social networks reinforce messages. Whether positive or negative, social networks reinforce whatever messages are circulating in the community. Positive messages among family planning users are strengthened through conversations with other users, but negative attitudes are reinforced among those with unmet need.

- Social barriers to family planning are significant. According to the baseline survey conducted in 2013 by Tékponon Jikuagou in the Mono-Couffo Department of Benin, 36% of women reported that it is not acceptable to talk about family planning in public. Gender norms often underlie negative attitudes towards family planning—for example, 8% of women and 17% of men believe that women who use family planning are promiscuous.

- Unmet need: Definitions matter. According to the baseline survey, only 13% of women believe they need a family planning method (and therefore would seek services). However, if we take a closer look at the data, parsing the results by perceived (by the woman herself) and actual (biological risk of pregnancy) unmet need, the data tell a different story. This view of the data suggests that over half of women (53.3%) who do not wish to become pregnant are at risk of pregnancy and need family planning.

If you want to learn more about the results from the household survey in Benin, take a look at the recent report here, available in English and French.

Learn more about Tékponon Jikuagou:

New Brief!: Overcoming social barriers to family planning use: Harnessing community networks to address unmet need (English, French)

Formative Research Report (English with French summary)

Baseline Household Survey Research Report (English, French)

For a list of additional reports, click here.

Where We Work

Where We Work  Press Room

Press Room  FACT Project

FACT Project  Passages Project

Passages Project  Learning Collaborative

Learning Collaborative  Search All Resources

Search All Resources  Social Norms

Social Norms  Fertility Awareness Methods

Fertility Awareness Methods